Saints in Our History

The Second Thousand Years

Return to

Index The Catholic Faith

Return To

Level Four Topic Index

Home Page

"Exactly as Christian communion between men on their earthly pilgrimage brings us closer to Christ, so our community with the saints joins us to Christ, from whom as from its fountain and head issues all grace and the life of the People of God itself" (Lumen Gentium, 50).

As the Church moved into the eleventh and twelfth centuries, one of its first concerns was reforming the corrupt clergy. Fortunately, the Church was blessed with several holy Popes, who were able to begin these reforms.

Other holy men began to reform the monasteries. The most important of these is St. Bernard of Clairvaux. As a young man Bernard joined a new monastic community known as the Cistercians, whose way of life was based on the rule of St. Benedict. But their way of life was simpler and stricter than that in most Benedictine communities of the time.

After he was ordained, Bernard was chosen to begin a new monastery following the Cistercian way of life. Bernard became the abbot of this monastery at Clairvaux and then founded sixty-eight more monasteries according to the same rule. The new generation of monasteries corrected many of the abuses that had crept into monastic life during the Dark Ages, and these monasteries were a great source of hope.

St. Bernard's own holiness was reflected in the life of Clairvaux and the other monasteries. He strengthened the faith by his sermons about devotion to Jesus and to his Mother. So great were these sermons that people from all over Europe came to hear him. Thus St. Bernard was able to rekindle the faith of the laity as well as that of his monks.

The Crusades

He had great influence on other matters in Europe as well. For example, St. Bernard preached the second Crusade, encouraging many people in France and Germany to join. The Crusades were the response of the Church to a new difficulty that had arisen because of the Moslems.

Toward the end of the eleventh century, the Moslems seized control of the Holy Land (Palestine) and persecuted those Christians who traveled on pilgrimages to Jerusalem and the other holy places. The crusades were military efforts to win back the Holy Land. They were carried on periodically during the next two centuries. The knights and soldiers who fought those battles for the cause of Christ used the Cross as their symbol. Many who either led or fought these Crusades were truly saintly men.

One of these courageous men was King St. Louis IX of France, who led the last two major Crusades. He is noted for being a holy man and a just ruler. His devotion to his faith was instilled in him at an early age by his mother. When he was growing up she often said to him, "I love you, my dear son, as much as a mother can love her child, but I would rather see you dead at my feet than that you should commit a mortal sin." Such lessons never left him, even when he became the king of France.

While he was king, he attended two Masses each day and spent much of his time in prayer. He frequently cared for the poor personally, often having them join his family at meals. And he taught his sons to love their faith as well. In his last words to his eldest son he wrote, ". . . the first thing I would teach thee is to set thy heart to love God".

For St. Louis, as for any saint, love of God came first. Thus, when it seemed necessary to fight a battle for Christ, St. Louis readily responded. He died on his way to fight his second Crusade. His last words echoed those of Our Lord on the Cross, "Into thy hands I commend my spirit."

Despite their great efforts, the Crusaders did not finally achieve their goal. The Holy Land was not freed from the Moslems. The Crusades did, however, strengthen the faith of many in Europe and increase devotion to Christ and his saints. They also opened western Europe to many areas of knowledge in which the Moslems had advanced - for example, navigation, medicine, and philosophy. This provided the basis for many scholarly and scientific achievements during the next few centuries.

The internal reforms of the Church, begun by St. Bernard and others, grew and flourished during the thirteenth century. This was the height of the period known as the Middle Ages.

New Religious Orders

During this century, two new religious orders were founded that were dramatically different from the traditional orders. The members of these communities did not live in monasteries isolated from society but lived instead in the town where they worked. Unlike the monastic communities, which owned large portions of land to support themselves, the new orders depended on the generosity of ordinary people for their basic needs. They are called mendicant orders, because they lived by begging. By living simply, these orders reminded Christians that the true role of the religious was to serve God.

The first of these communities was the Franciscan order, which was founded in Italy by St. Francis of Assisi. Francis, the son of a wealthy merchant in Assisi, grew up with plenty of money, which he spent recklessly. He wanted to become a knight but realized that Christ was calling him to serve God in the religious life. Francis then decided to live as a poor man, discarding his fine clothes for those of a beggar and caring for the needy and the sick.

He began a life of prayer - preaching and serving the poor. His holiness attracted many young men, who joined him in his work. Eventually Francis wrote a simple rule for his followers. With the Pope's blessing they were established as the Order of Friars Minor ("Little Brothers"). By the time of Francis' death, there were over five thousand Franciscans in Europe.

Men were not the only ones attracted to Francis' way of life. A rich young woman from Assisi also asked to join him, and thus with Francis' help St. Clare established a community for women, who also lived according to the Franciscan rule.

Another mendicant order for men was founded by a young Spanish priest, Dominic de Guzman. This order is known as the Dominicans, or Order of Preachers. As a young priest St. Dominic was sent to convert a group of heretics living in southern France, the Albigensians. To help him in this task, he gathered a group of young men who were willing to dedicate themselves to preaching. Like the Franciscans, they lived in simplicity and poverty. They spent their time in teaching and preaching. The Dominicans emphasized scholarly learning for their members, so that they would be able to preach more effectively. Consequently, many of the great university teachers of this age were Dominicans.

St. Thomas Aquinas

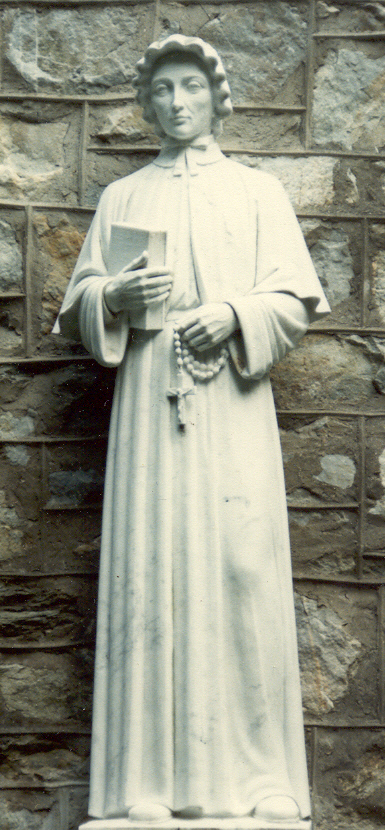

The greatest of these Dominican scholars and teachers was St. Thomas Aquinas. Thomas was born in Italy in 1225 A.D. and began his education at the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino. His wealthy family hoped that one day he would become a Benedictine. Thomas went on to study at the University of Naples, where he first met the Dominicans. Their simple life of poverty and study attracted Thomas, and, despite many vigorous objections from his family, he joined the order.

He studied theology and philosophy with another Dominican, St. Albert the Great, and eventually became a teacher himself at the University of Paris.

Thomas studied the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, whose writings were among those brought back to Europe by the Crusaders. St. Thomas used Aristotle's ideas in his own work in theology. He taught that God's revelation to man is not contrary to reason but, rather, that reason is necessary to understand God more completely. While his method was based on Aristotle, his insights were based on the Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers. He wrote a large number of books, but the best known and most important of these is his Summa Theologica. In this famous book he organized, explained, and defended all the doctrines of our faith. Thomas' writings have never been surpassed in the Church and remain today among the most important sources for Catholic theology.

Although Thomas' scholarly works were important to the Church, it was his love of God that made him a saint. His devotion to Christ and the Blessed Sacrament are reflected in some of the beautiful prayers and poems he composed for certain feasts. For example, St. Thomas wrote the beautiful hymn Pange Lingua ("Sing My Tongue"), the final verses of which are frequently sung at Benediction. Christ and the Church were the center of St. Thomas' life, and he knew that his writings were unimportant compared to the infinite wisdom of God.

In 1274 A.D. St. Thomas was asked by the Pope to attend the Church council in Lyons, France. While on his way he became ill and died on Marcy 7, 1274. Before he died, he displayed his humility and love for God. As he prepared to receive the Eucharist for the last time, he said:

I receive thee, price of my redemption, Viaticum of my pilgrimage, for love of whom I have fasted, prayed, taught, and labored. Never have I said a word against thee. If I have it was in ignorance and I do not persist in my ignorance. I leave the correction of my work to the Holy Catholic Church, and in that obedience I pass from this life.

St. Catherine of Siena

Although the Church flourished in the thirteenth century, it suffered many problems in the centuries that followed. During the fourteenth century debates between the Popes and the kings of France created a major crisis. For the first time since St. Peter, the Pope was not in Rome. For seventy years the Popes lived in the French city of Avignon. It was a woman from Siena, Italy, who finally persuaded the Pope that he must return to Rome.

St. Catherine of Siena was a young lay-woman who had chosen to live a life of prayer and service to others, particularly the sick. Her reputation for holiness spread throughout Italy, and many people turned to her for help and advice.

Several times Catherine wrote to Pope Gregory XI, urging him to return to Rome for the good of the Church. Finally, she visited him in Avignon, pointing out to him that many of the Church's problems stemmed from the absence of the Popes from Rome. Pope Gregory listened to her, returned to Rome, and began to reform the Church. Catherine died only a few years later at the age of thirty-three. Because of her many spiritual writings, Catherine was declared a Doctor of the Church.

Although St. Catherine helped the Church end one crisis, another, even greater, followed almost immediately. For the next forty years there were two men, one in Avignon and one in Rome, who claimed to to Pope. This confusion, known as the Great Western Schism, divided the Church and weakened the role of the Pope. By the time it was resolved, the Church's unity was threatened.

Protestant Reformation

The fifteenth century also brought with it many new developments. This age is known as the Renaissance (rebirth) because of the renewed interest in the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. During this time many of the clergy were once again corrupted by money and other luxuries. Also, the invention of the printing press made it possible for new ideas - some heretical - to spread more rapidly. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Church was once more in need of reform.

Unfortunately, some attempts to reform the Church led the "reformers" away from her. This is known as the Protestant Reformation. Beginning with Martin Luther, several groups rebelled and broke away from the Church. This was the beginning of the many Christian denominations we see around us today.

This tremendous upheaval was the reason that the Church called the Council of Trent. The Church did need reform, and she also needed to clarify the doctrines that were being challenged by the Protestants. The work of this council strengthened the Church so that she emerged from her latest crisis stronger and more able to face the work ahead.

The period immediately following the council is known as the Counter-Reformation. Just as new religious orders had helped the Church to reform during the Middle Ages, likewise new religious orders helped the Church to renew herself at this time. For example, the Ursuline sisters, dedicated to teaching young women, were formed by St. Angela Merici. The most important of these new communities was the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola.

St. Ignatius of Loyola

St. Ignatius was a Spanish nobleman who was trained to be a soldier. During his career, he became noted for his bravery and loyalty to his king. In one battle he was seriously wounded and required several months' rest. During this time he read the only books that were available to him - a life of Christ and some lives of the saints. By the time his leg had healed, his life had changed. St. Ignatius vowed to become a "soldier" in the service of Christ and his Church.

After a time of spiritual retreat, Ignatius began to study theology to prepare himself for his new work. While he was studying at the University of Paris, he was joined by other young men, and together they made their first vows of poverty and chastity. After a few years they formed themselves into an order and offered their services to the Pope.

The special work of the Society of Jesus was to defend the faith and serve the Church in whatever way or place the Pope asked them. At the beginning this took the form of defending the faith against the attacks of the Protestants. For example, many Jesuits were sent to Germany to preach against Lutheranism, and they were successful in bringing many people back to the Church. As time passed, the Society began to establish its own universities, convinced that a strong Catholic education would ensure loyalty to the Church.

The motto of St. Ignatius and his Society was "Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam" ("to the greater glory of God"). He really lived only for God's glory, and that eventually made him a saint.

Missionaries to the New World

In the centuries that followed, the Church, strong and healthy once more, began to spread even further. The European nations had begun to explore and colonize territories in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The Church also was active, spreading the faith to the people in these areas. The greatest missionary activity since the early days of the Church followed the Reformation.

One of the greatest missionaries at this time was a Jesuit, St. Francis Xavier. He was among the original members of the Society of Jesus and was chosen by St. Ignatius to be one of the Society's first missionaries. Like the great missionary St. Paul, Francis covered a vast territory in a very short time.

His preaching began in India. From there he traveled through Sri Lanka, Malaysia (Indonesia), and Japan, converting many as he went. He died before he could enter China, but future Jesuits who continued his work did preach the gospel in China. The work begun by St. Francis Xavier paved the way for later missionaries to the Orient.

Jesuit missionaries from France were among those who brought the message of Christ to the French territories in North America. St. Isaac Jogues and seven others are called the "North American martyrs". They preached among the Indians and suffered martyrdom for their faith.

Spanish missionaries labored in the southwestern and western portions of the North American continent. One of the most notable is the Franciscan priest Fr. Junipero Serra, who founded a series of missions among the Indians in California.

With the work of the missionaries and Catholics who settled in America from Europe, the faith was planted on American soil. The first saint born in the United States was St. Elizabeth Seton, who was born in 1774.

Elizabeth was raised as an Episcopalian and married William Seton, a prosperous merchant from New York. They had five children. When Elizabeth's husband became ill with tuberculosis, they moved to Italy, were he died. In Italy Elizabeth became convinced that the Roman Catholic Church was the true Church.

When she returned home, Elizabeth became a Catholic, despite the strong objections of her family and friends. To support herself and her children she opened a school for other young children in her vicinity and later in Maryland. Her school was unusual because it was intended for any student, not just the children of the rich. This was the beginning of the Catholic school system in the United States.

Other young women joined her. In time this group became a religious community, the Sisters of Charity. Founded in 1809, this was the first religious order to be founded in America.

During this time of missionary expansion, the Church was challenged by the scientific, intellectual, and political revolutions taking place in Europe. The Church was constantly called upon to defend herself but was able to remain strong.

Modern Times

As the Church entered the twentieth century, she was blessed with a saintly Pope, Pius X. A simple country priest, but also a great teacher, Pius was able to help the Church face one of the greatest heresies in her history - Modernism. Modernists think that teachings on faith and morals should change and evolve, and that there is no unchangeable, objective revelation from God on which Christianity is based. In addition, modernists deny the reality of supernatural events, such as miracles, which support the Christian faith. Pope Pius X wrote two great encyclicals summarizing and refuting these ideas.

Pope St. Pius X served as a great shepherd of the Church. He encouraged frequent reception of Holy Communion. He reminded Catholics that the Eucharist is our spiritual food. He also lowered the age at which young children may first receive this great sacrament. In addition, Pope Pius X encouraged the Catholic laity to become involved in charitable work among the poor. He died broken hearted as the First World War began, expressing his simplicity in his last will and testament, "I was born poor, I lived poor, I die poor."

Since his death, the Church and the world have faced more challenges - particularly the spread of atheistic, totalitarian forms of government in various nations. The two world wars since the death of Pius X remind us of the terrible evils of Nazism, communism, and fascism. In opposition to these evils, one of the great saints of this century, St. Maximilian Kolbe, shines forth as a example for our times.

Maximilian was born in Poland near the turn of the century. As a member of the Franciscan order, he devoted much of his time and intelligence to understanding the role of Our Lady in our salvation. Before he was ordained, he organized a group of the friars into what he called the "Knights of Mary Immaculate". Members of this group dedicated themselves to win the whole world for Mary. After his ordination, he also gathered lay people into his group. In order to spread his message further, in the early 1920s he began a magazine called The Knight of the Immaculate. He had no financial backing, but the magazine thrived surprisingly, although it continually faced financial difficulties. He also established a community in Nagasaki, Japan, which later miraculously survived the atom bomb.

In 1936, after establishing the community in Japan, Maximilian returned to Poland. At this time Hitler came to power in Germany, and soon his armies invaded Poland. Maximilian was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned in Auschwitz in 1941.

Maximilian was immediately a source of strength for all imprisoned with him. Shortly after he arrived, some prisoners escaped from the camp. In retaliation, the Nazis randomly chose ten prisoners to be starved to death. One man who was chosen, Sgt. Francis Gajowniczek, began to cry for his wife and children. At this point Fr. Maximilian asked the guards if he could take the sergeant's place. When asked why he chose to do this, he answered, "I am a Catholic priest." With that Maximilian Kolbe began the road to his martyrdom. He prayed and gave courage to the other nine men in the starvation bunker. To the complete surprise of the Nazi guards, he was still alive after three weeks of neither food nor water, and they finally killed him. St. Maximilian died as he had lived - offering his life to God.

In our times the Church continues to grow, as the faith is spread in places such as India and Africa. After two thousand years we see that the Holy Spirit continues to guide the Church. Christ's promise continues: ". . . the powers of death shall not prevail against it."

Used with the permission of The Ignatius Press 800-799-5534

Return to

Index The Catholic Faith

Return To

Level Four Topic Index

Top

Home Page